Ellis Woodman

The Architecture of James Gowan:

Modernity and Reinvention

2008

The Architecture of James Gowan: Modernity and Reinvention is a comprehensive chronicle of the entirety of Gowan’s work, exploring his involvement in some of the most important and influential buildings in post-war Britain.

Based on extensive interviews conducted with award winning architectural critic Ellis Woodman, The Architecture of James Gowan profiles Gowan’s impressive career.

The Architecture of James Gowan further features many of the architect’s freehand drawings and sketchbook notations, displaying his critical eye, humour and wit, alongside a selection of his own writings. The Architecture of James Gowan: Modernity and Reinvention is a comprehensive reappraisal of the career of one of British architecture’s most influential and yet unsung figures.

On Langham House Close

EW: How did the two of you end up in practice together?

JW: Well, he got his hands on a big job - the Ham Common housing - that he couldn’t do. Stirling informally tutored a student at the AA called Paul Manousso. Manousso’s dad purchased the Ham Common site with outline planning permission for 30 flats and he invited Stirling to put in a scheme. Stirling used to slip out of the office (Lyons Israel Ellis) and dash down to see the client and slip back again. This was an office where everyone was watching everyone. He was a big chap. I don’t know how he managed it.

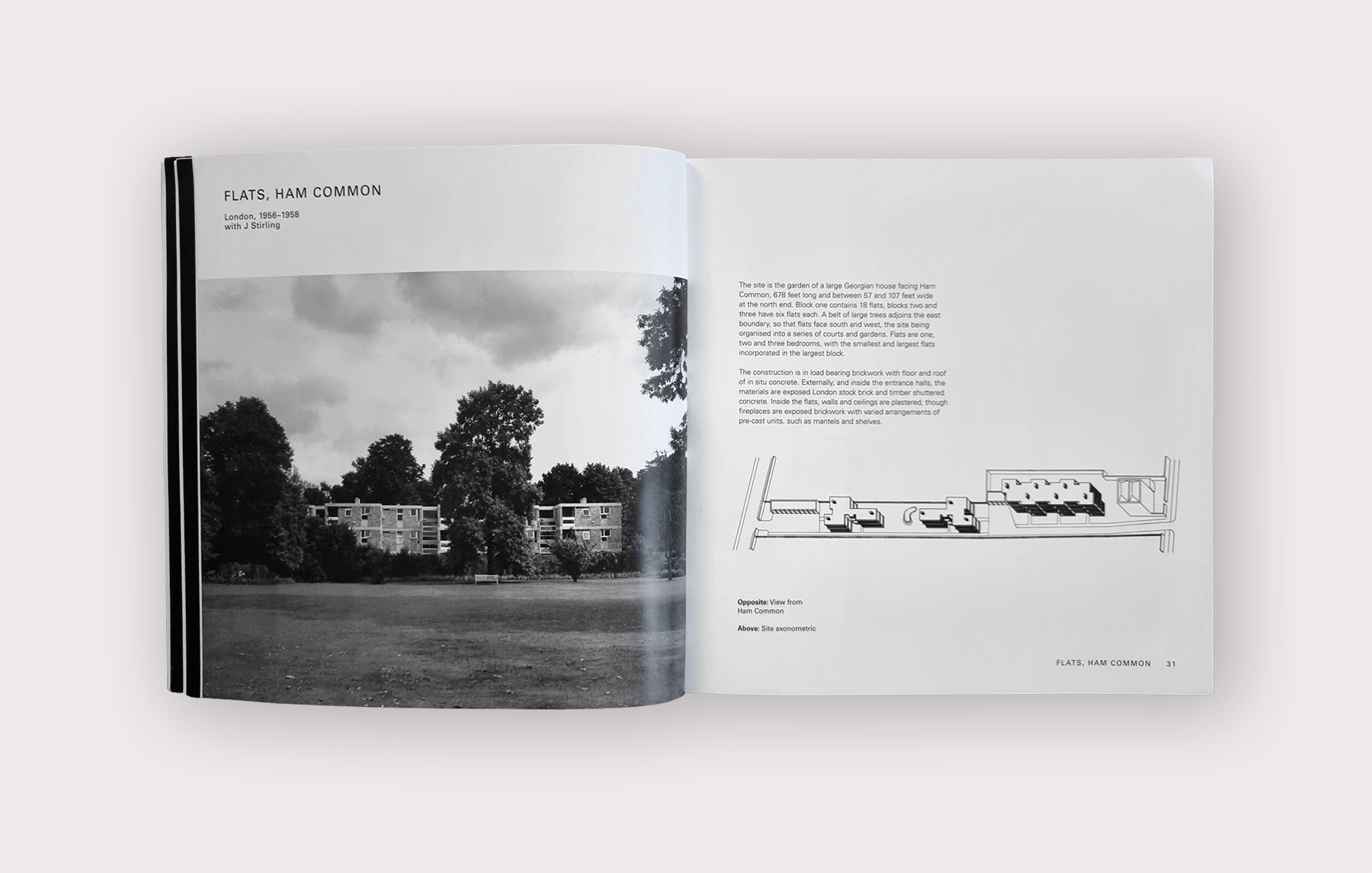

He produced a scheme with a block of apartments and a terrace of houses and a road that went straight through the site front to back. He put in for planning permission and they turned it down because of the daylighting angles of the narrow part of the site, where the terrace was. Then he lopped a bit off the back of the terrace at an angle because it notionally complied with but they chucked that out too. At this point he told me that they had got this second refusal, taht the client would be hopping mad. This was at the end of the week and on Monday he was going to see the client and chuck the job in. I said that I’d have a look at it. He passed it over and at the weekend I produced a scheme that dropped the through road and replaced the terrace with the little apartment clusters we ended up with. I came on the Monday with the plan forms sketched out and Stirling took them along to Manousso. They put the application right away and got it passed.

EW: So, the two of you handed in your resignations at Lyons Israel Ellis?

JW: Stirling insisted that we gave in notice together because he thought what is going to happen if I resign and he won’t come? We had no contract. It was all verbal. It was all gentlemanly as far as I was concerned but neither of us were gentlemen.

EW: On Ham Common, did the fact that you were working for a developer afford you greater licence than if you had been working in the public sector?

JW: Oh, yes. With the doctrinaire nature of bureaucracy, this would never have got through.

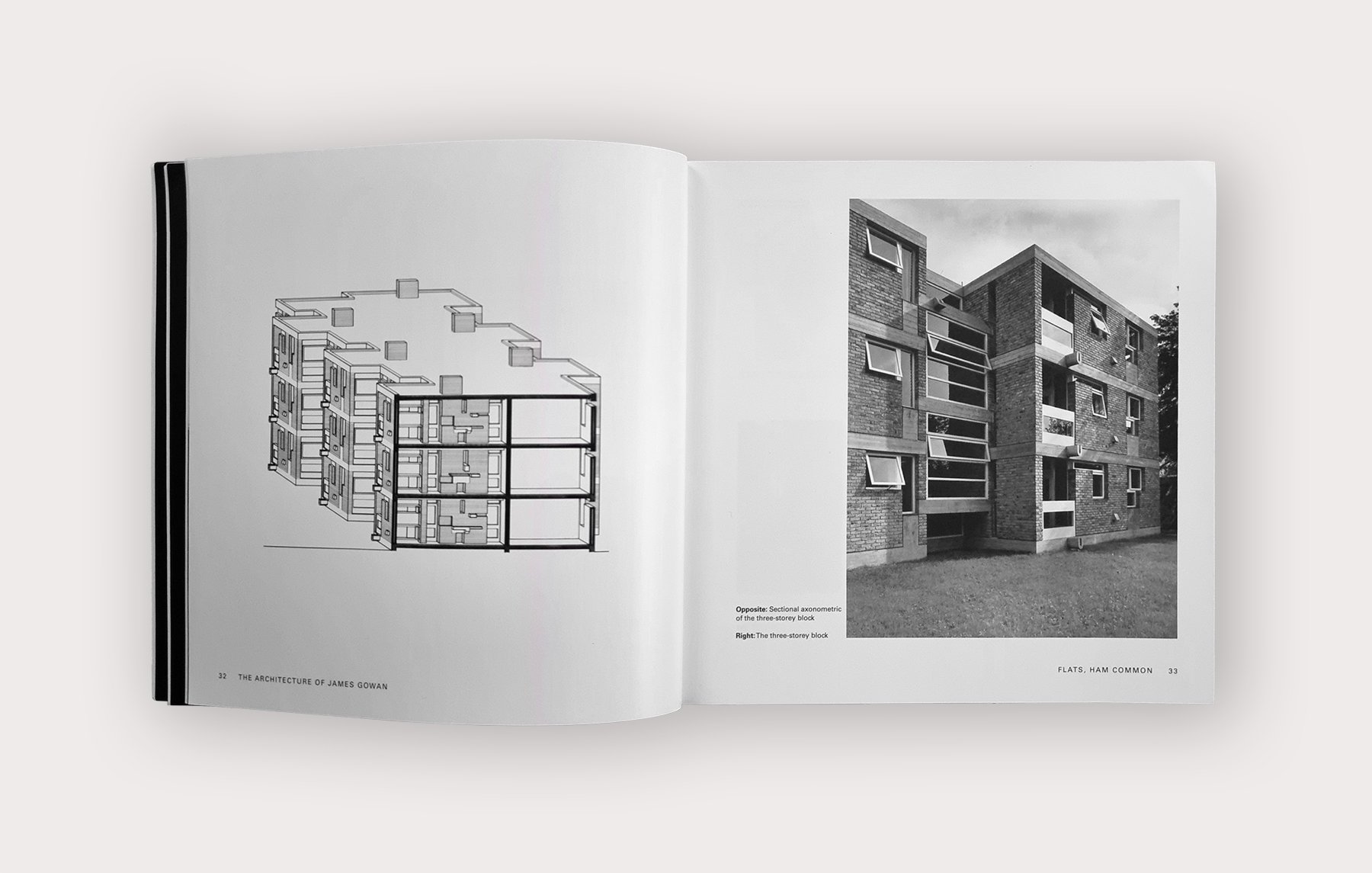

EW: A characteristic of your domestic designs from the 1950s and 60s is that the fireplaces are located centrally. This approach heightens the presence of the hearth although it also engenders plans that are unusually deterministic about how furniture should be arranged. The fireplaces tend to be freestanding but at Ham Common, the modest dimensions of the apartments presumably precluded such an approach and so you have partitions to either side. Nonetheless, the fireplaces’ central location and their chimneys’ articulation in bare brick and concrete gives the hearth a powerful rhetorical charge.

JW: When you put a fireplace in the middle, you may not get a free-plan but metaphorically, you do. Manousso worried that what we were doing was unduly dramatic but one of the reasons that he was employing us was that we were better judges of what a young professional might like.

EW: With its interiors of undisguised brick and concrete, Ham Common often gets labelled as an example of the New Brutalism. Did you feel your work sat within an emerging tendency?

JW: No. Neither Stirling nor I wished to be bracketed like that. The term seemed to convey an intention to shock which certainly wasn’t in my scheme. There were things about Brutalism that I did find attractive but they were rather simpler, earthier lessons than you would get from from Reyner Banham who seemed intent on directing the notion towards a savageness in going about things. What appealed to me was the idea that if you were, say, designing a kitchen you might buy in apparatus out of a catalogue. it hadn’t be processed by an architect to be agreeable and you forfeited the notion that had designed everything, but you got expertly built stainless steel fittings and saved yourself a fortune. Intellectually, that represents quite a difference from the Italian dream that you design everything from top to bottom - the handles on the doors, the light switches, and so forth.